trippen x RMIT: Material-Driven Design Collaboration

In January 2016, while leading a fashion and textiles design study tour to Paris, a colleague and I chanced upon the Trippen shoe store on rue de Saintonge. As luck would have it, founder and Managing Director Michael Oehler was in town; while we browsed the collection he explained the brand and its sustainable ethos.

Enchanted by their story and in love with the distinctive and beautifully crafted shoes, we exchanged business cards, and, with new shoes in hand, went on our way. The seed had been sewn for what was to become a valuable collaborative relationship between Trippen and the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT University.

A Berlin-based company, Michael Oehler founded Trippen with Angela Spieth in 1992. Recognising the negative environmental and social impacts of large-scale off-shore manufacturing, their goal was to produce distinctive fine-quality shoes with production units small enough to guarantee environmental standards, and ecological manufacturing techniques and create well-paid local jobs with good working conditions.

The material, stylistic and emotional durability of the shoes was also a principal concern and their modular aesthetic – what might be described as the Trippen DNA – afforded their deconstruction for repair; a valued service for loyal customers who wish to prolong the life of their beloved shoes. Trippens really are shoes for life.

The following year I led another study tour, this time to Berlin, where Michael and his son Karl kindly provided our fashion and textiles design students with a tour of the Trippen factory. Located one hour north of the city in a small town called Zehdenick, we followed them through the factory’s many rooms as they explained their production process. Every aspect was informed by the most ethical and sustainable values, from the leather to the finished shoes.

Stitching rubber soles to leather uppers at the Trippen Factory in Zehdenick.

At the end of the tour, we passed a room full of boxes containing thousands of leather remnants from the pattern-cutting process – the one problem Trippen were yet to solve. In conventional terms, these pieces were fashion waste, but a respect for their materials and the animals from which the leather was derived meant they felt unable to dispose of them - but what to do?

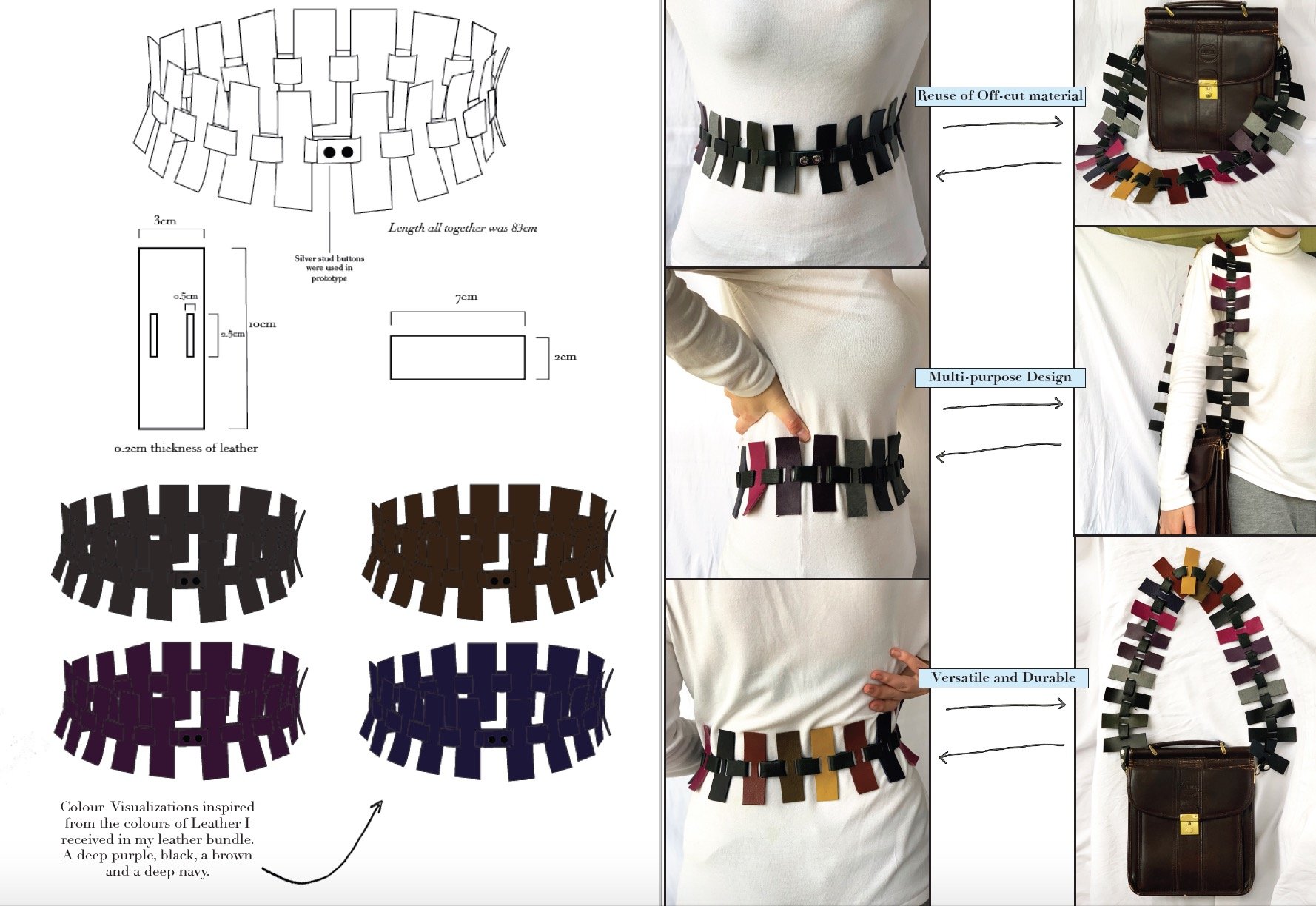

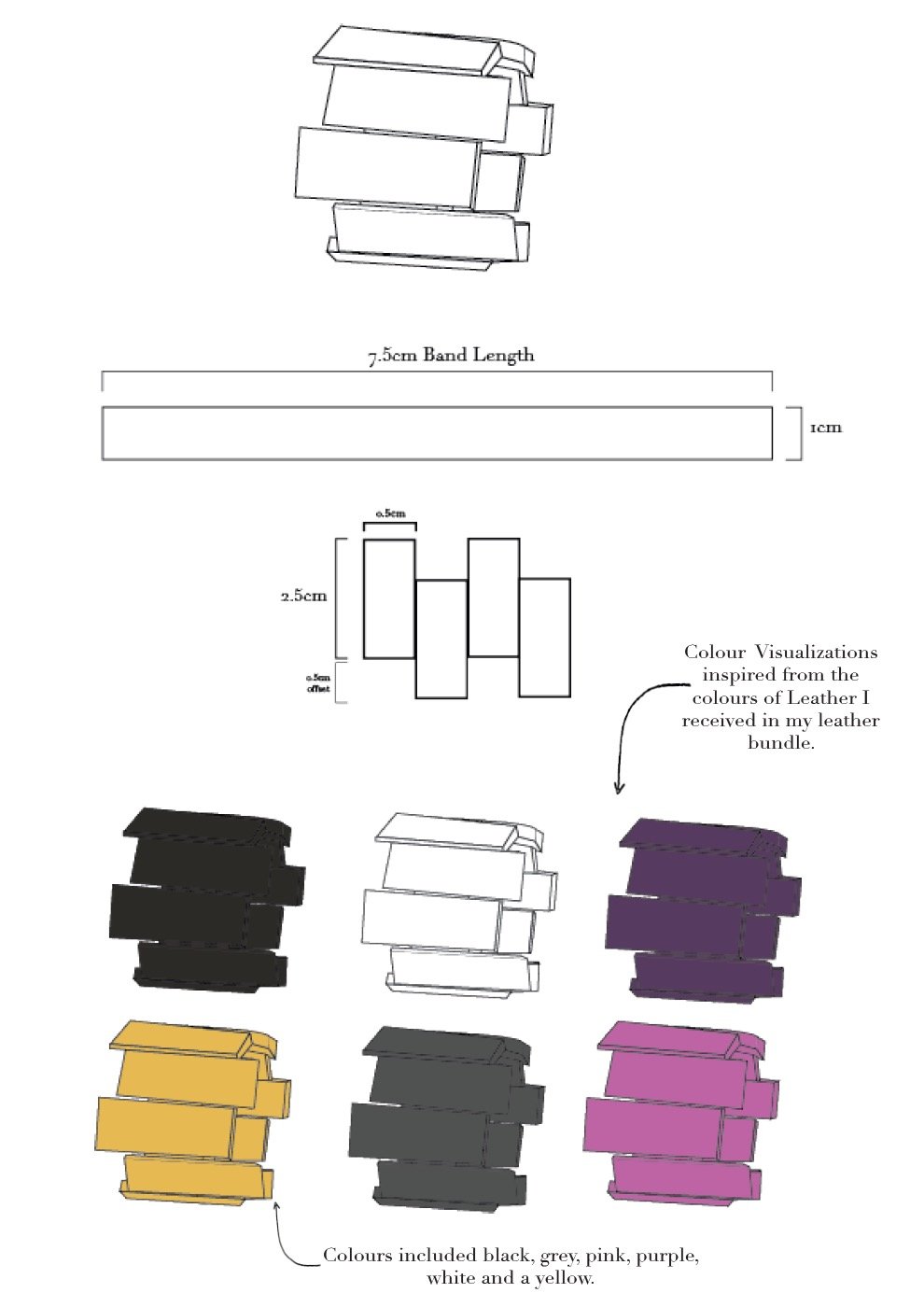

Michael suspected some kind of accessories were the most likely solution since many of the pieces were often small, awkwardly shaped and varied in colour and quality. While they had previously produced rings from the pieces, a more substantial and scalable solution was needed to use a larger proportion. This seemed like an opportunity just waiting for its time to emerge.

In 2018, with sustainability as a central focus, the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT embarked on a project to overhaul all its programs and courses. I took responsibility for Fashion Design Body Artefacts and Accessories, a 12-credit optional course available to students in the Bachelor of Fashion Design program.

An opportunity to use the leather remnants had finally arrived.

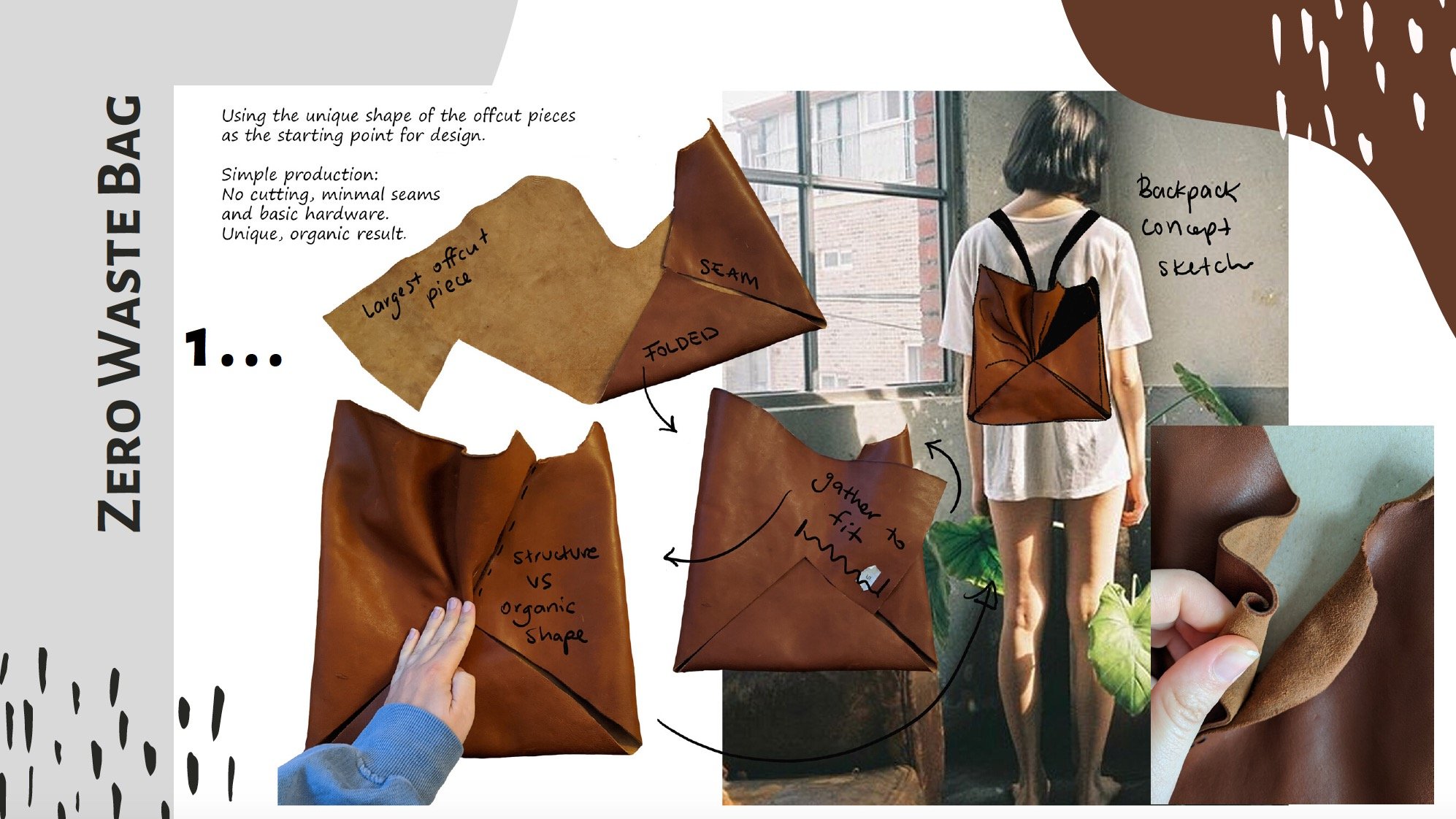

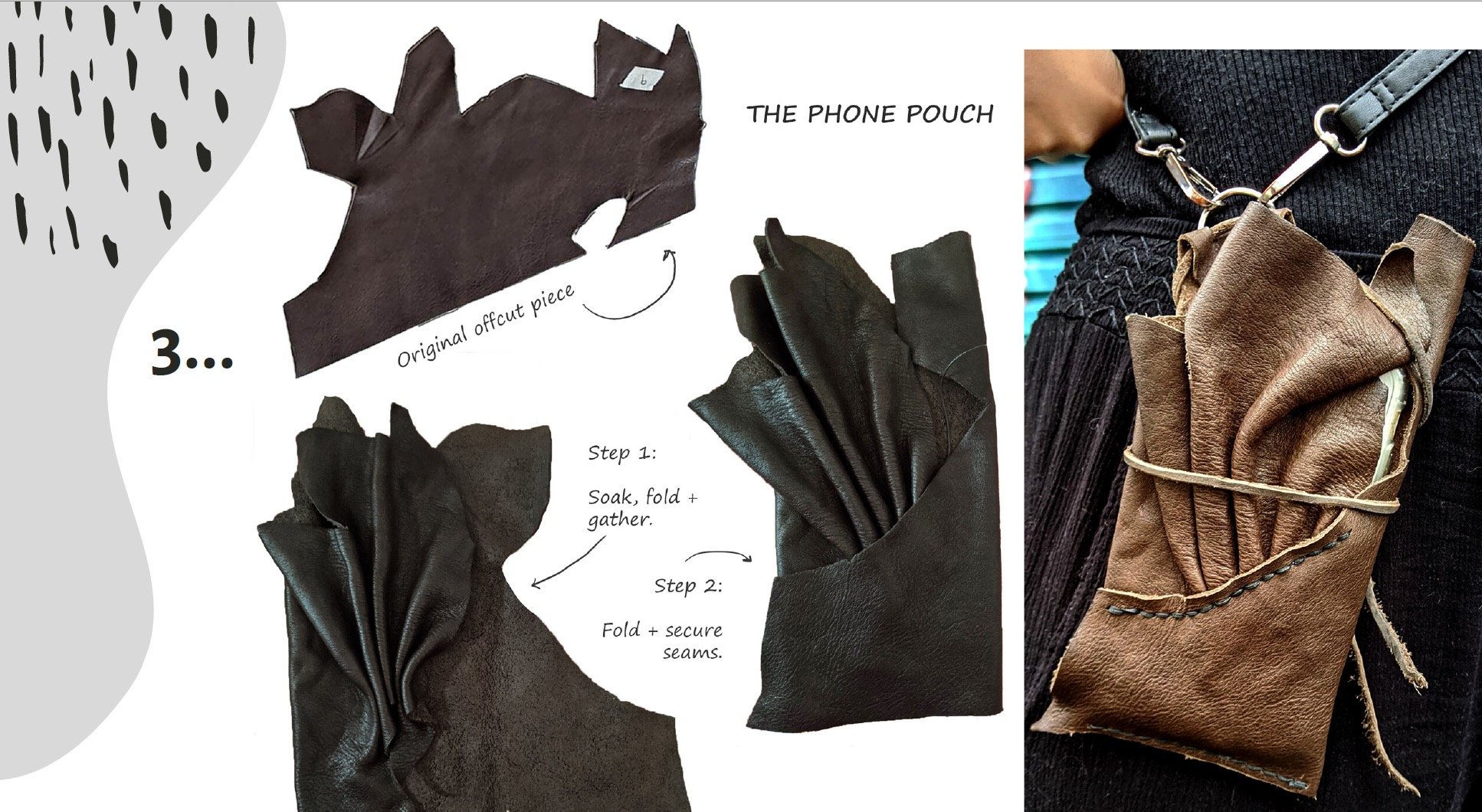

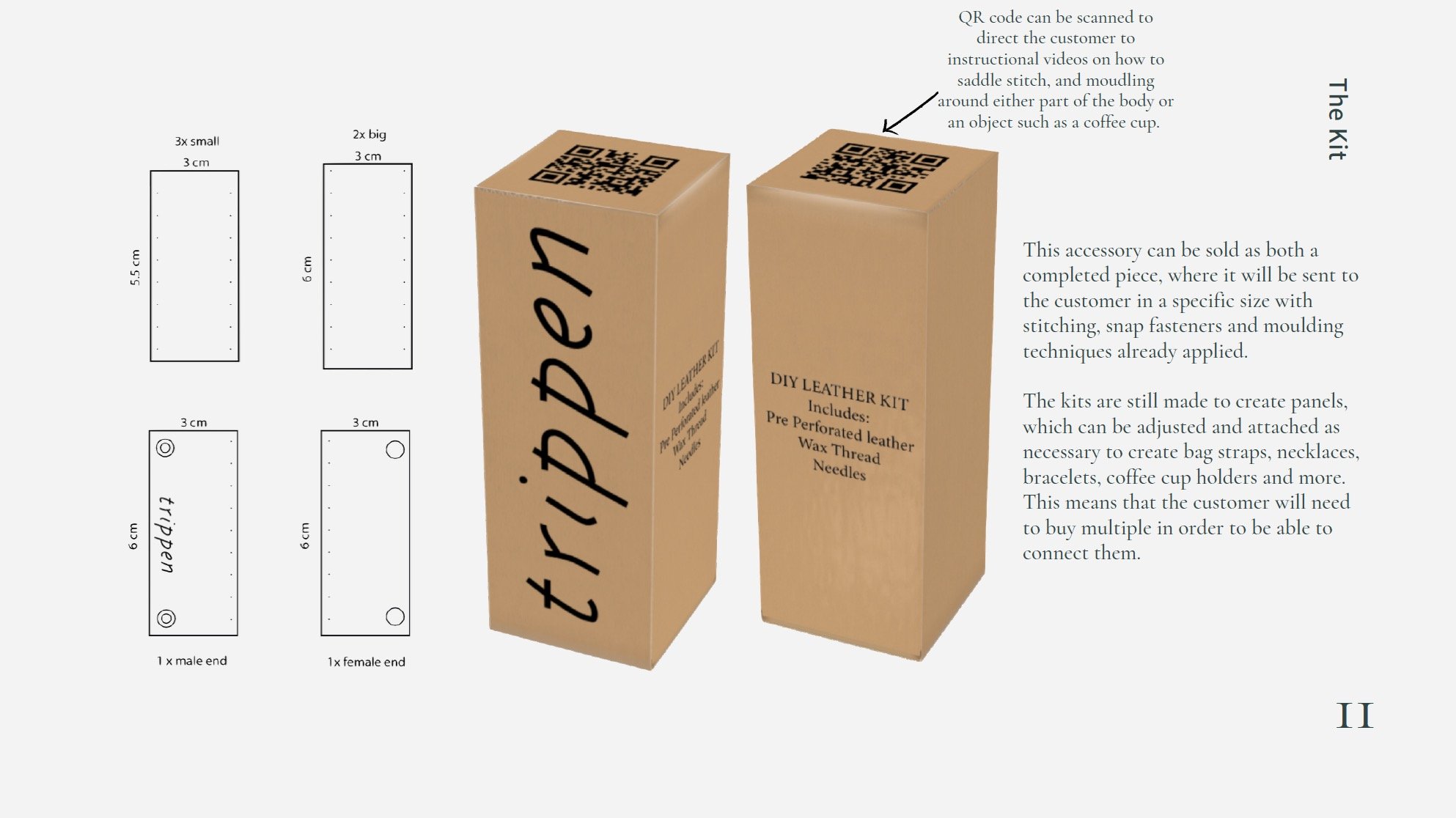

Applying theories developed during my PhD research, I designed content and assessments that would enable students to develop a ‘material-driven’ approach to design. Rather than finding materials to realise a preconceived design idea (often sketches informed by design conventions), the materials would provide a starting point to guide and inspire the design process.

Trippen shipped bundles of leather, one for each student comprising a wonderfully unique collection of random sizes, shapes and colours. It was like Christmas when the packages arrived – a true gift for each of the students – and the unpredictability of the varied materials was an exciting challenge for us all.

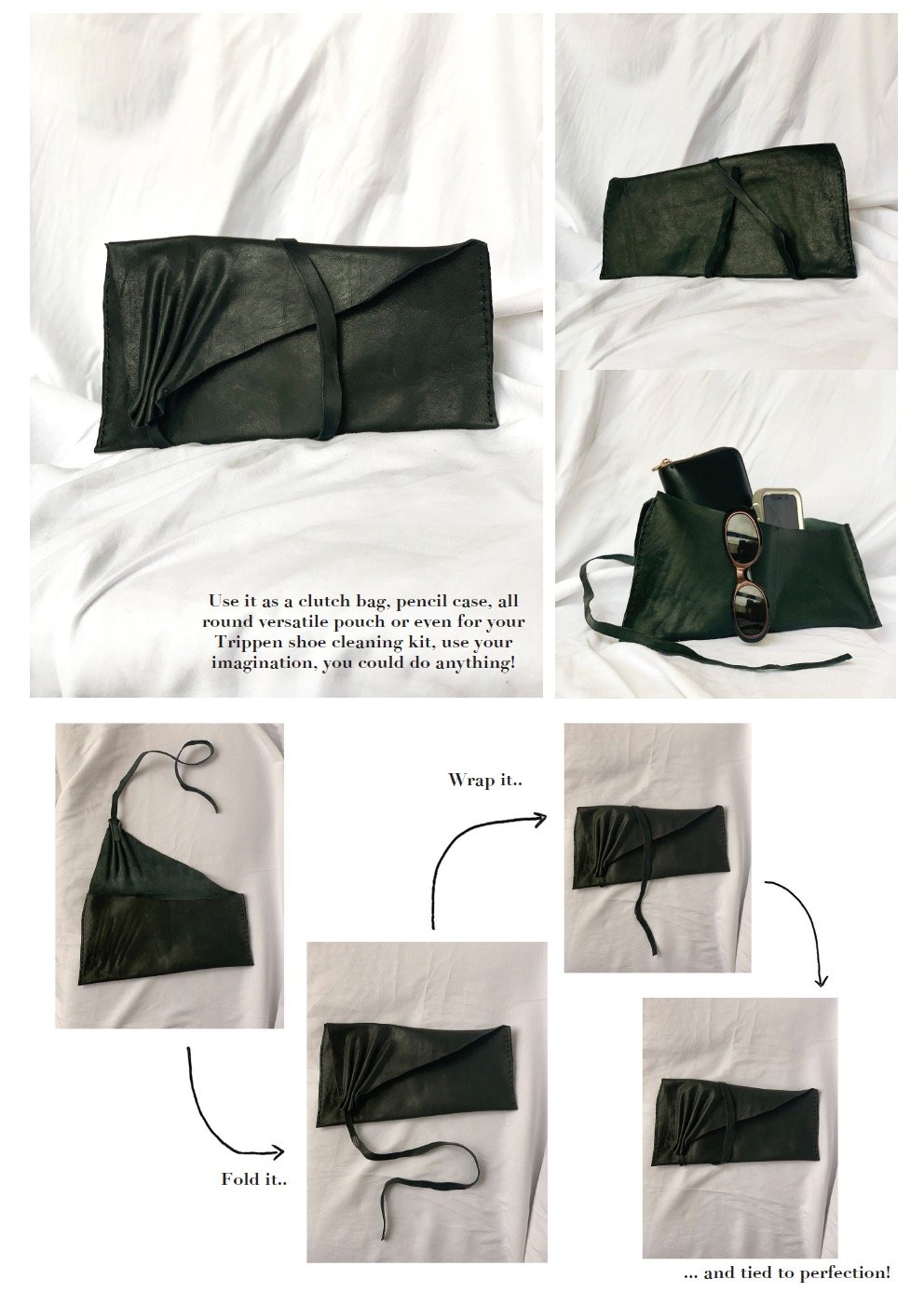

Following an initial assignment to activate a perception of material affordances (the ‘This is Not a Shoe’ activity), students were encouraged to experiment and play with the leather pieces to see what forms emerged. Leather-working techniques such as moulding and sewing were introduced and other craft techniques and tools were researched to help manipulate the materials. Students were also encouraged to use sustainable processes that would fit with the brand’s circular ethos and afford the future deconstruction, repair, recycling and reuse of the materials.

The identity of Trippen shoes is very much entangled with their materiality, from the beautifully sculpted Alder, Beech and rubber soles, to the vibrant vegetable-tanned leather, bold stitching and raw external seams. Video-recorded interviews were conducted with loyal Trippen wearers (many of them design staff at RMIT) which provided a means for students to acquire an understanding of the brand’s most loved design features and wearers’ sensory engagement with the materials.

Evocative descriptions of the ways the sculpted soles and soft leather uppers wrapped, hugged and supported the feet provided a range of verbs and adjectives to inform experimentation with technique, form and placement.

The project took place at the very beginning of Covid and while the students were disappointed not to have full reign of the School’s newly equipped Makers Spaces full of laser cutters, 3-D printers and other state-of-the-art technologies, the restrictions of making do with the tools they had to hand (and repurposing everyday objects as tools) had the unexpected benefit of further developing their material literacy and creative problem-solving skills – important transferable skills for future careers in sustainable design. While students often found the constraints posed by the materials and tools frustrating, the rewards from persisting with these challenges ensured a truly collaborative process where both materials and students were able to transform one another.

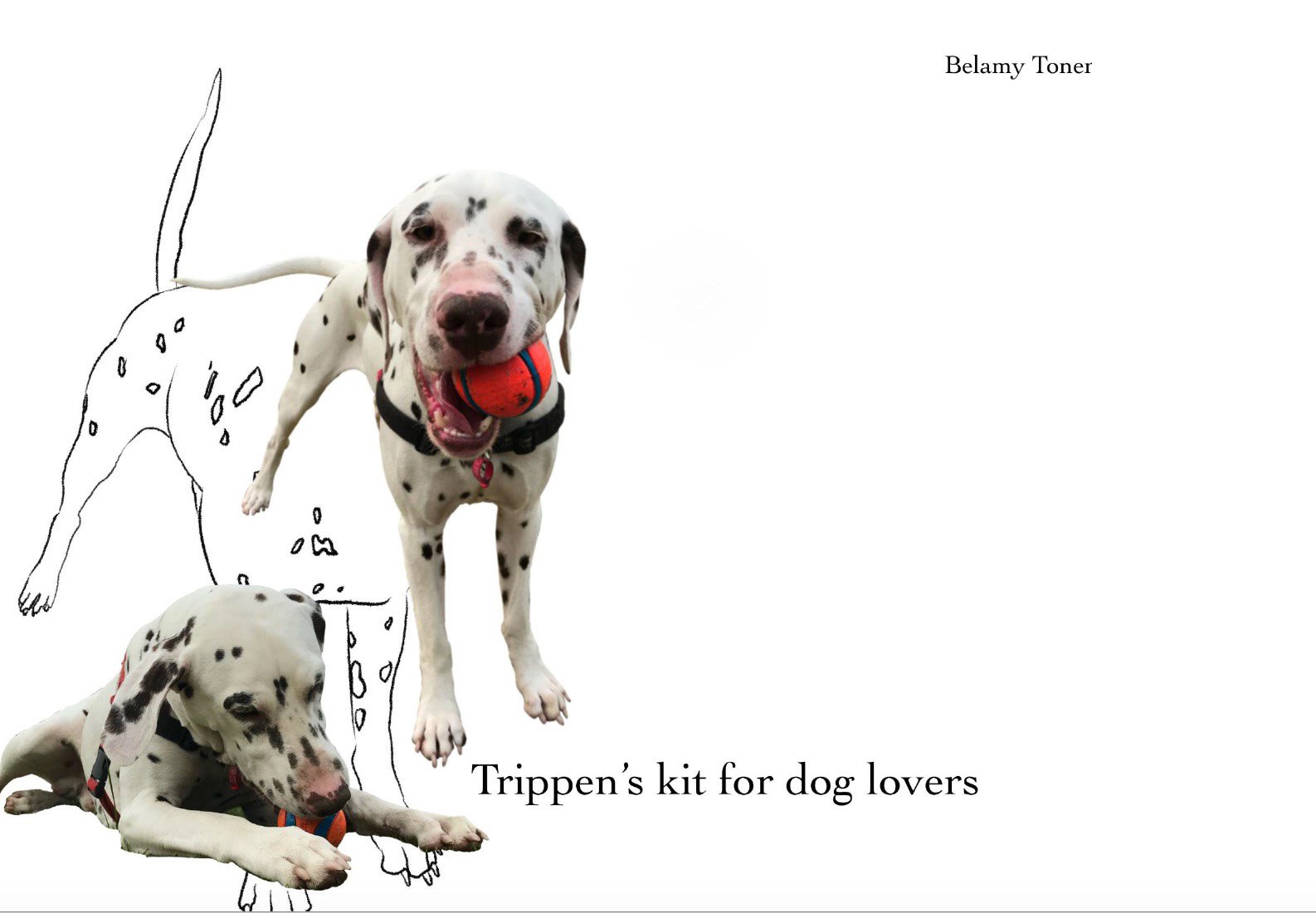

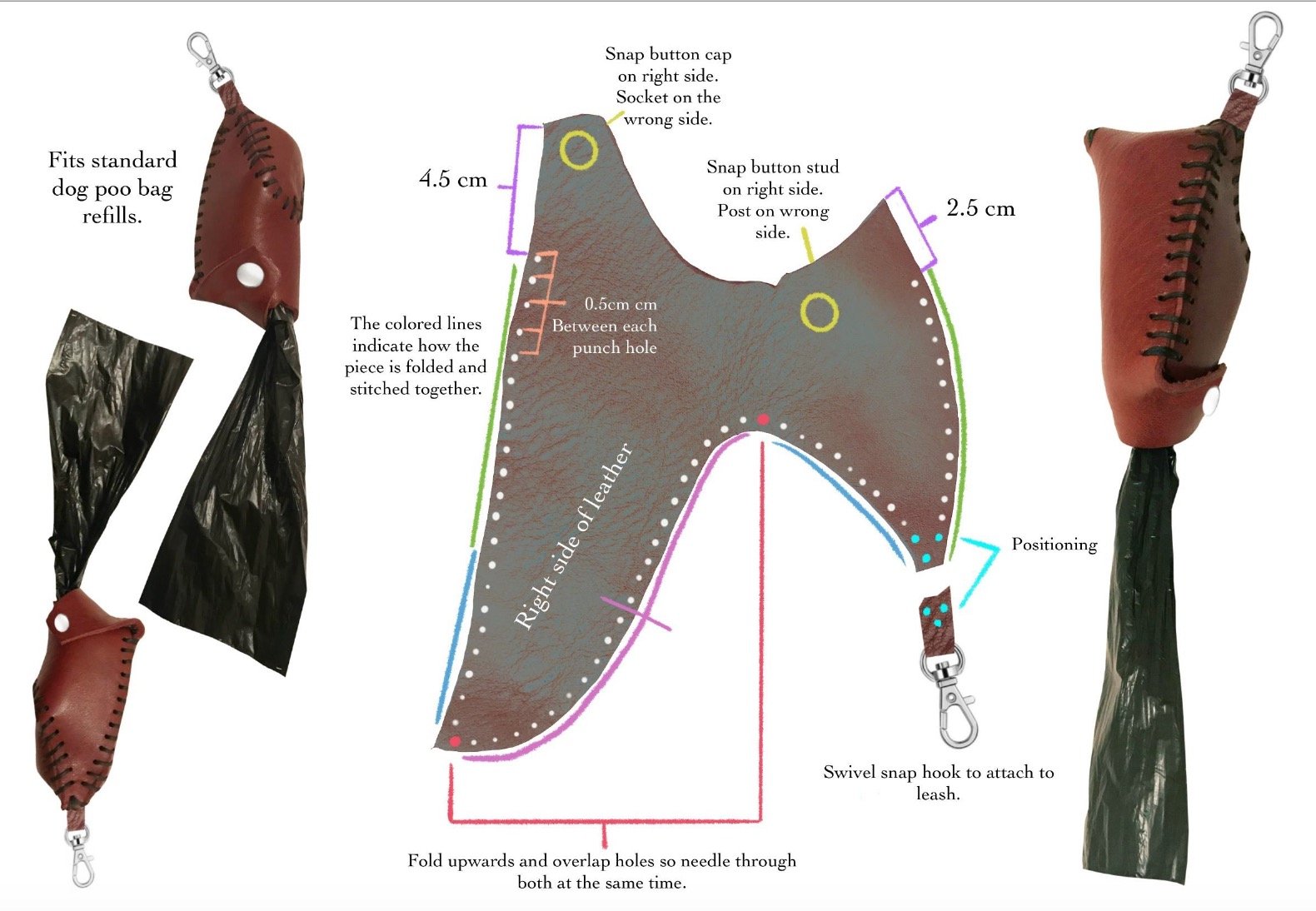

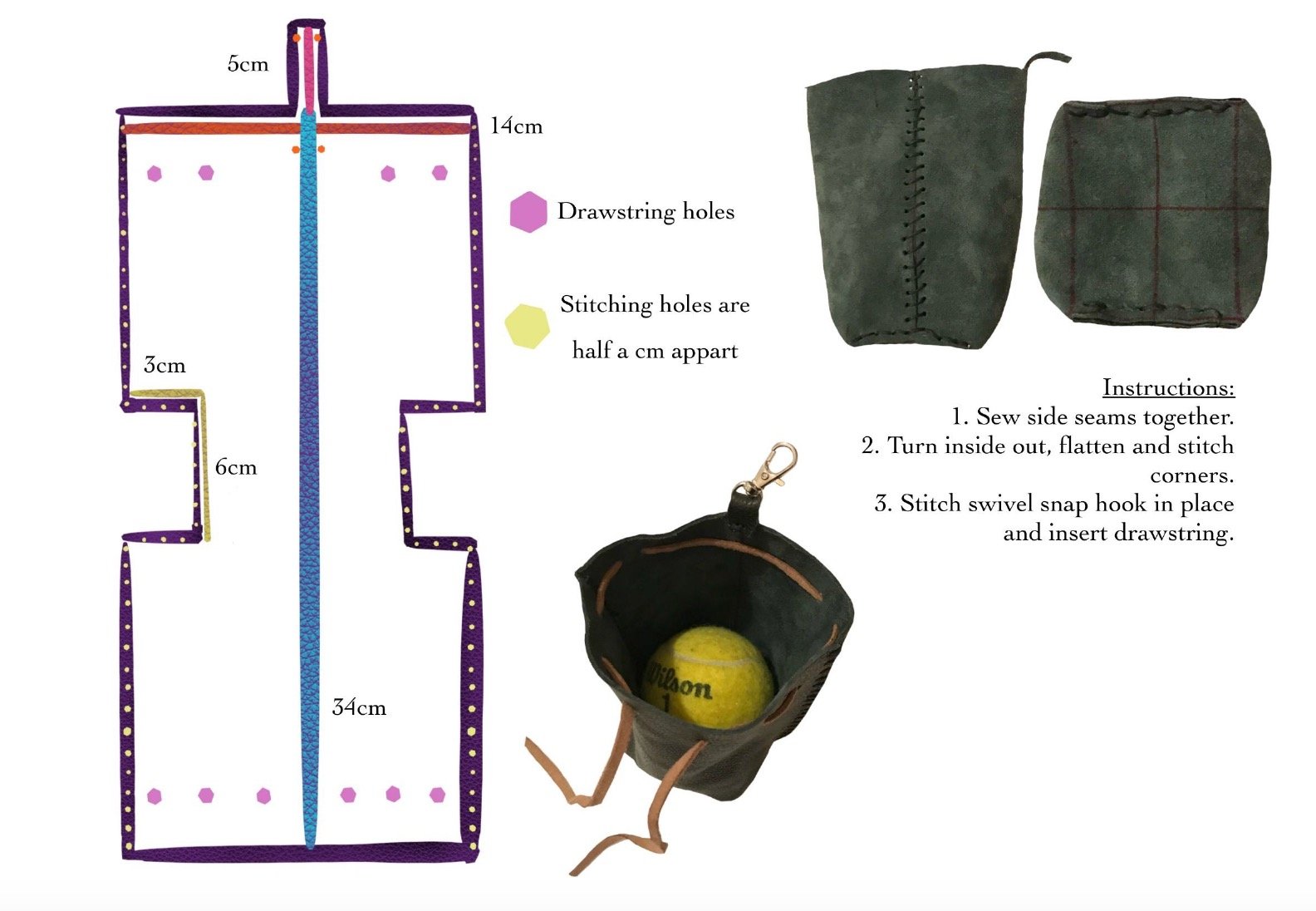

At the end of the project, a shortlist of designs were judged by Trippen and the winners were validated with cash prizes and the possibility of production. My personal favourite was a Trippen dog poop bag dispenser, which, although not selected, would undoubtedly have been a stylish accessory for the increasing number of dog owners at the time!

On reflection, while the project was a success, the constraints of remote learning during Covid were challenging. The impacts of the pandemic on the footwear Industry at the time also constrained Trippen’s ability to develop and produce the students’ ideas. Nevertheless, an associated research project enabled us to analyse and develop the assignments for enhancing sustainable material-driven approaches to design.

By disseminating the project and sharing the research, we hope the legacy of the collaboration will continue in other contexts and forms.

Examples of student outcomes

Zoe May Sutherland - 2020

Lucie Twyford - 2020

Amelia Carlisle - 2020

Belamy Toner - 2020